Worst of Winter Over? Fading La Nina Could Mean a Warmer 2023

"Past performance is not an indicator of future results" the old financial disclaimer goes. The same can be said about our weather, which has been unusually mild in recent weeks. Prevailing jet stream winds high overhead have been streaming in from the moderately cool Pacific, and not the battery-draining tundra of Siberia - thus the slush in your driveway.

There is no question in my mind that the Northland will experience a few (real) cold fronts in late February and March. But as the sun angle continues to rise the potential for week after week of subzero weather begins to diminish in March. Not impossible, but rare. We'll see more subzero weather, but in terms of duration and intensity, the most bitter winds of winter are probably behind us now. The heaviest snow too.

La Nina, a phase of cooler water in the equatorial Pacific, is part of ENSO, the El Nino - Southern Oscillation. This is a natural cycle - going from cool (La Nina) phases to warm (El Nino) phases, that can nudge weather patterns thousands of miles downwind, impacting both temperature and precipitation close to home. La Nina tends to keep the Northland colder. Not always, but there is a correlation.

An unusual 3-year long La Nina cool phase is ending, and reliable models that predict future sea surface temperatures (like the one above from IRI, the International Research Institute) are predicting an 82% chance of "ENSO-neutral" by spring and I see a possible swing in the cycle toward El Nino warming later in 2023. If (and this is a really big if - this actually happens it would increase the potential for consistently milder weather next winter). Low confidence at this point, but my gut tells me that's the direction we're going.

La Nina winters tend to be colder from the Pacific Northwest into the Upper Midwest, but significantly milder over the southern US.

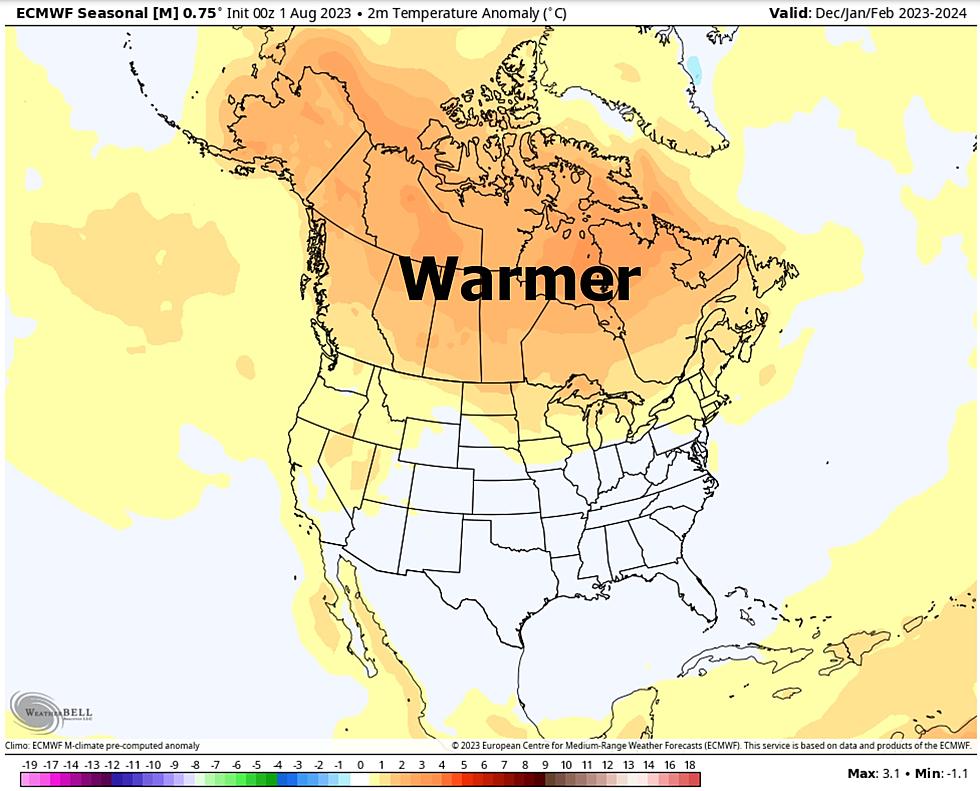

There is a strong correlation between El Nino warm phases in the Pacific and milder winters for roughly the northern half of the USA - generally drier for the Northland, with battering storms for California and the West Coast, something we've seen recently (during a La Nina phase) which has me scratching my head.

Abnormally mild weather is forecast to linger into most of next week with a string of 30s, even a few days at or just above 40F, which is no small feat for mid-February in the Northland.

After a 3-year run, La Nina is finally easing, and there is a statistically significant chance we may slide into a milder El Nino pattern by the Winter of '23-24. Statistically, we are due for a warm winter. It would be ironic if the unusual winter warmth we've witnessed in recent weeks was only the appetizer. The main course may come next winter.

LOOK: The most expensive weather and climate disasters in recent decades

More From KOOL 101.7